Once there was a woman who could never get green things to grow, no matter how hard she tried. Each spring, she would sow seeds she had gathered in the autumn. Her pockets and bags bulged with little zip-lock plastic bags; the kinds that had once contained screws, sequins, spare buttons and the like, or else had been intended for the safe disposal of coronavirus testing kits. Into these vessels she would pour the findings from her autumnal wanderings, shaking seedheads and snapping open seedpods she had gathered from verges, waysides and overgrown student gardens. And, before the first buds broke out on the beech trees, she would sprinkle her scavenged treasures into prepared pots and trays on the windowsill, draw a deep breath and wait…

And, sometimes, germination would occur – that little miracle that never failed to amaze and keep the germ of hope alive within her. But sooner or later, the seedlings would wilt and wither, victims perhaps of too much or too little water or sun or of the wrong sort of potting medium. If a seedling ever grew large enough to plant out, it would never last for long. Perhaps a slug would eat it or a cat dig it up, a child would trample it, or a builder empty a bucket of cement over it, or it would simply fail to thrive. Plants acquired from garden centres and farmers’ markets suffered much the same fate, despite careful consideration about where to position them.

When summer arrived, the cloud of disappointment over the spring’s failure would lift, for now was the time to propagate plants from cuttings. With the sun shining down encouragingly, the woman would snip off new shoots from old shrubs, sprinkle their stems with rooting powder and hope and pop them into the empty pots recently vacated by the failed seedlings, lining them up in neat rows in her cold frame. But by October, the cold frame would have become a tomb, the once verdant cuttings transformed into shrivelled little grey sticks. If by then, she began to lose hope of ever becoming green-fingered, she would notice the seedheads, rattling and bobbing in the autumn breeze, and remember that it was seed-gathering season once more.

Thankfully, there was plenty of existing greenery in the garden. The woman and her husband had inherited a well-kept, mature garden when they had bought their house, and it contained many plants and trees that had been planted and tended by other hands, in other times. But it had been a few years since they had moved in, and the garden was no longer in quite such a healthy state. Shrubs that had bloomed during their first year failed to flower again, despite careful pruning in accordance with the next-door neighbour’s instructions, while others seemed to get devoured by pests the moment the woman looked the other way. Most of the time, she would shrug off these horticultural shortcomings, putting them down to bad luck or inexperience. But there were times when she would curse and wonder if she might in fact be cursed. At times like these, she would think back to a certain February day, long ago, when she had cut down the elder tree…

The elder tree had grown in a graveyard, and the woman had cut it down because a man called Russell had told her to. She had been a volunteer on a conservation day, and he, the expert. Had she had any doubts about carrying out his request, she was reassured by the pleasing onomatopoeia of his name. She had always enjoyed aptonyms – words that aptly describe the occupation of their owners – and what better name for a man who spent his days in the woods than Russell?

The elder had been marked for death because it had outgrown the shady confinement of the thicket behind the gravestones and dared to encroach across the path into the realm of the living, clutching and scraping at passers-by with its bony twigs and ragged buds. Undaunted, the woman had gripped her handsaw in her Gortex-gloved hands and sawn right through the elder’s slender, furrowed trunk. And, as if in protest, the elder had released puffs of its dank, bitter scent into the chill air with every saw stroke.

It was months later that the woman felt a budburst of regret. She had gone on a guided walk around another green space in her local patch and learnt all about the uses and folklore of the trees that grew there. The guide, whose name was Liz, had paused beneath an elder tree, a hint of mischief in her eyes. Elders were generally straggly things that never normally grew beyond bush size, but this one had been allowed to flourish into a small tree. It was June, and the elder’s branches were laced with frothy, sweet-scented blossoms that hummed with the harmless buzz of hoverflies.

You should never harm an elder tree, Liz warned the group, for they were the favourite haunts of fairies and other supernatural beings. Fairies have long memories and vengeful hearts, and destroying their homes was the surest way to invoke their wrath. The woman had given a nervous laugh, then followed Liz to the next tree.

* * * * * * * * *

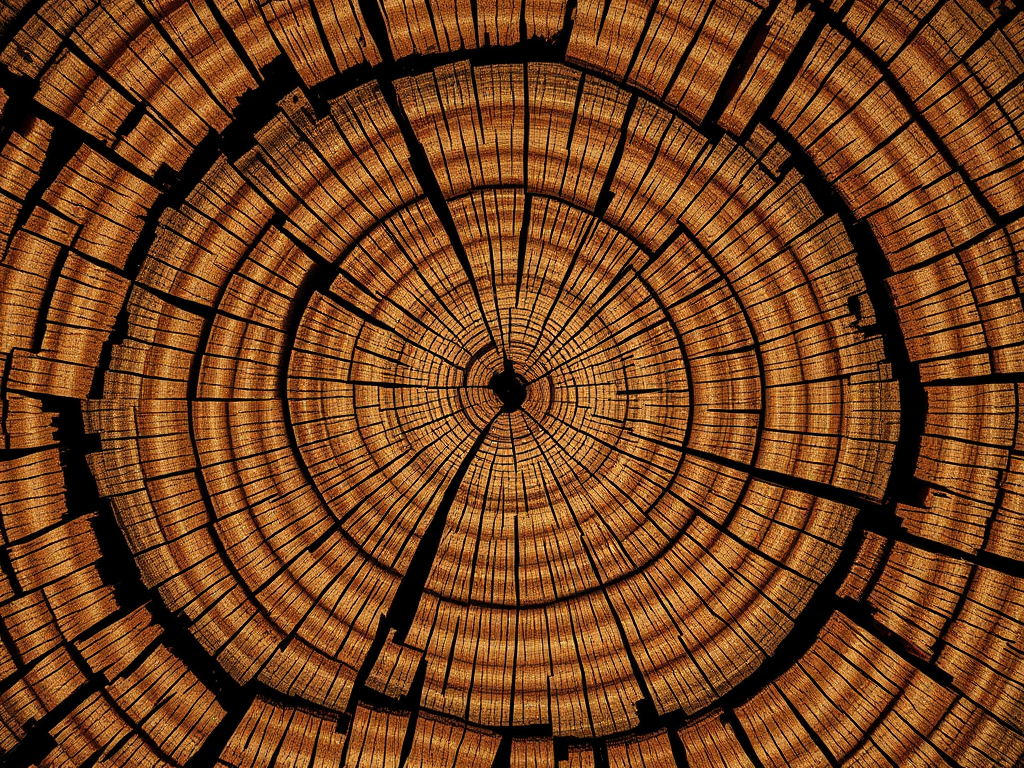

Russell was a rational, practical man. He had studied botany and arboriculture and spent his whole life working with trees. He could identify hundreds of different trees, both native and non-native, and at all times of year, both from a distance by their silhouettes and up close by the texture of their bark and the shape and positioning of their leaves along their twigs. He lived and thought and breathed and dreamt in trees. It was as if sap and not blood flowed through his veins, and his years on earth were marked by rings around his heart and not lines around his eyes. He knew exactly when and how to plant a tree, where it would thrive and not become a nuisance to his fellow humans and where others before him had lacked such foreknowledge. In other words, he knew which trees to root for and which to root out…

It was thanks to Russell that his district was so leafy; he had planted and cared for nearly half the trees that grew there. But of course, he had not done so alone. His work was dependent on the drifts of volunteers who signed up every week, hoping to escape the treadmill of modern life and reconnect with nature for a single afternoon. Despite Russell’s quiet ways and soft voice, these volunteers did his bidding unquestionably, his deep passion for trees radiating from his being like an invisible network of mycelia beneath the ground.

The volunteers were an odd bunch. Retired, sprightly schoolteachers in mismatched ensembles; office workers in branded sports gear; hippies in hand-knitted jumpers; lycra-clad fitness fanatics; and anorak-wearing conservationists – all with different ideas about the world. Russell was a rational man, yes, but he was also a kind and patient one, and he was not so completely closed-minded as to believe that there was nothing in this world beyond our finite human understanding. And so, when the volunteers spoke, as they often did, of trees in myth and legend, Russell would listen, albeit with only half an ear. In this way, he learnt that yew trees were symbols of death and immortality; that rowan boughs were once thought to ward off witchcraft, and that the word ‘Druid’ derives from the Celtic word for ‘oak’. And he learnt that fairies dwelt within the branches of elders, and accordingly, it was unwise to cut them down.

Of course, Russell did not believe in any of this nonsense; he was a rational man after all, but he was also a practical one, and he knew that it was better to be safe than sorry. Elder trees frequently grew in the wrong places throughout the district’s green spaces and needed to be removed. But he did not do the removal. There was no sense in risking destroying his life’s purpose by angering supernatural forces, whether he believed in them or not. And so it was that Russell always made sure it was the volunteers, and never himself, who cut down the elder trees…

A fascinating story! I never knew that about elder trees (or the origin of the word Druid!).

LikeLike